Following World War I, Futurism gained new members and assumed different formal qualities, including those of arte meccanica (machine aesthetics). While mechanized figures and forms had appeared earlier (in the art of Fortunato Depero, for example), Ivo Pannaggi and Vinicio Paladini articulated the principles of this idiom in their 1922 “Manifesto of Futurist Mechanical Art.” Enrico Prampolini also adopted a mechanical language at this time, and he subsequently expanded and signed the manifesto, publishing it in his journal Noi in 1923.

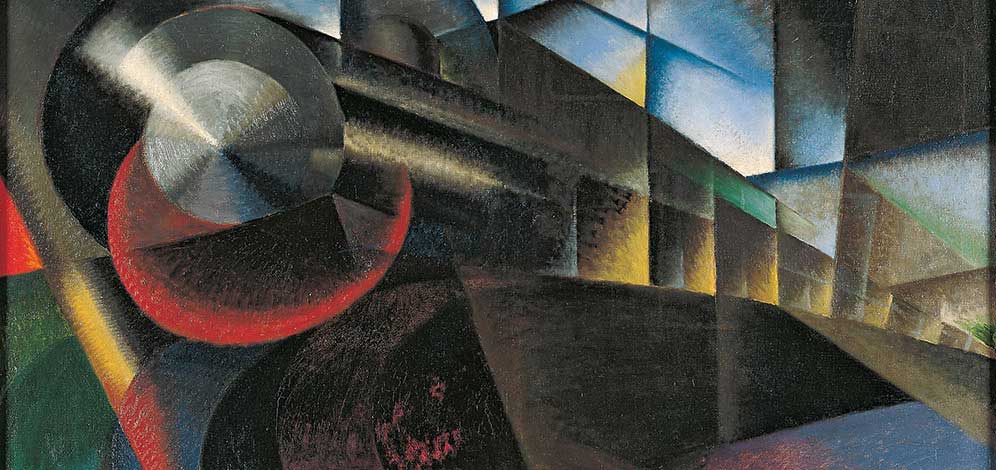

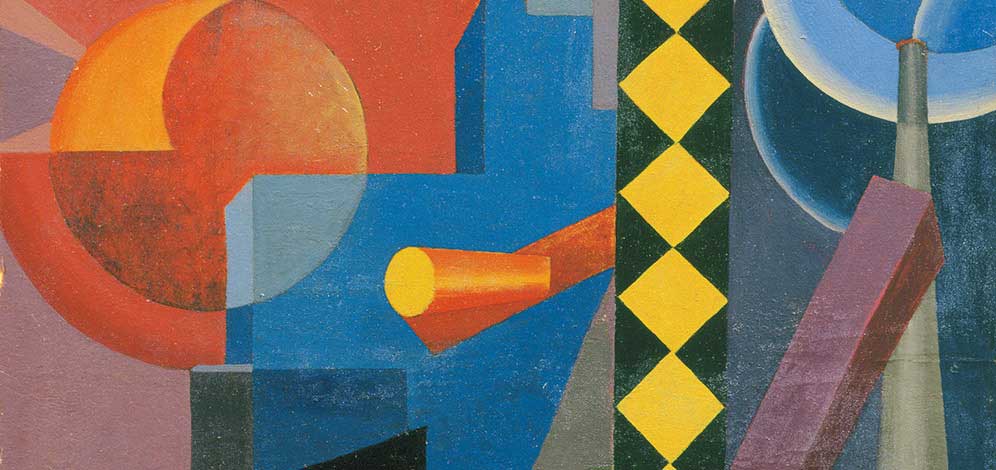

Pannaggi’s Speeding Train (1922) demonstrates the Futurists’ sustained interest in the locomotive as a symbol of modernity, motion, and the machine. The painting depicts a powerful train barreling toward the viewer at a diagonal angle. Speeding Train suggests the total sensory experience of observing the daily trains passing through the small coastal towns along the Adriatic (the blur of the moving cars, the clamorous noise of the motor, the ear-splitting scream of the whistle).

Later, Pannaggi’s interest in machine aesthetics led him to integrate Constructivist elements such as beams, cubes, cylinders, and three-dimensional letters into his work. In 1932–33 he attended the Bauhaus in Germany, the only Futurist aside from Nicolaj Diulgheroff to do so.