The years leading up to World War I are often called Futurism’s “heroic” phase. In this era colored by optimism, the Futurists worked in a mature avant-garde language; their compositions edged toward abstraction and they reinvented traditional artistic forms. The group also acquired members beyond the initial Milan–Rome axis. In Florence, for example, Giovanni Papini and Ardengo Soffici became involved with the movement. Their journal Lacerba (1913–15) published history-making exchanges on Futurism.

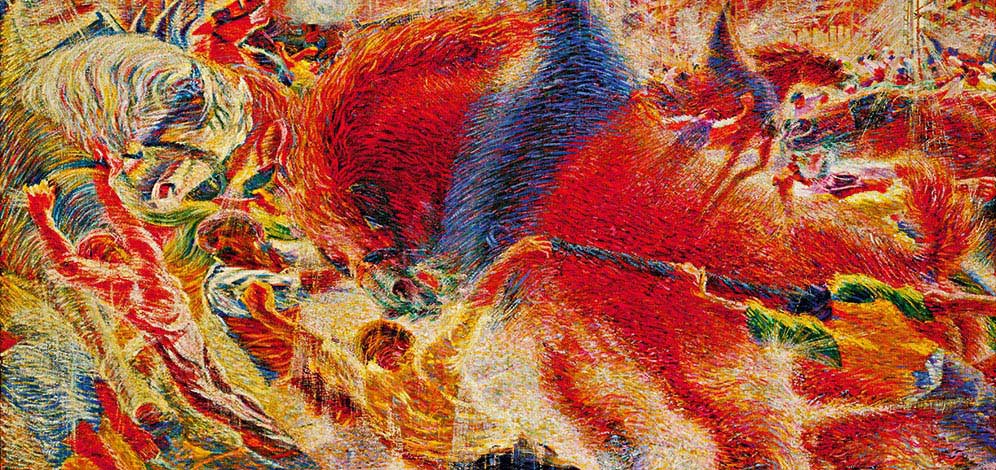

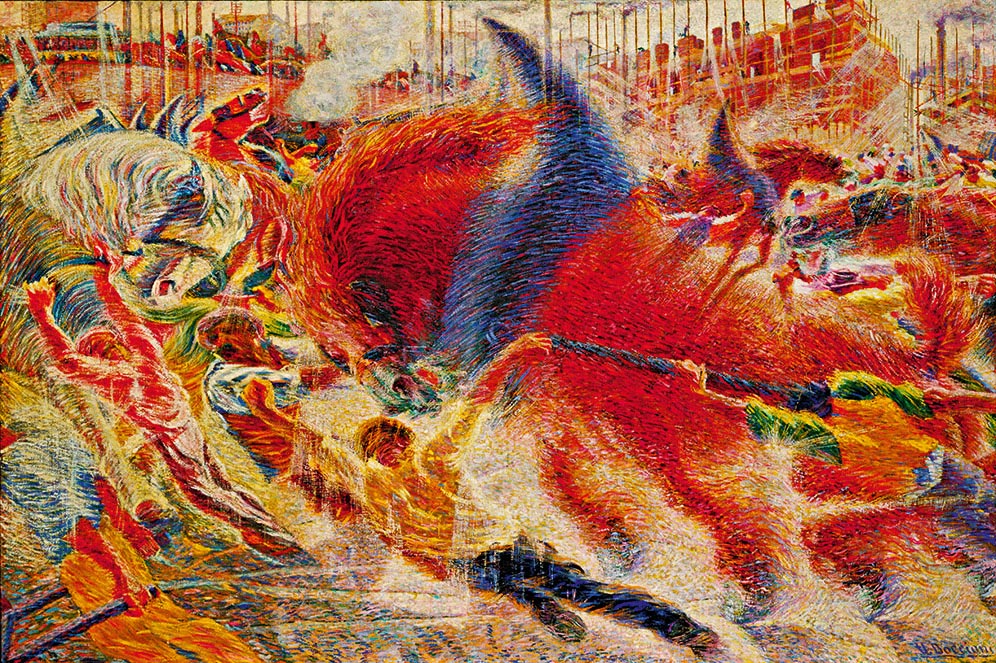

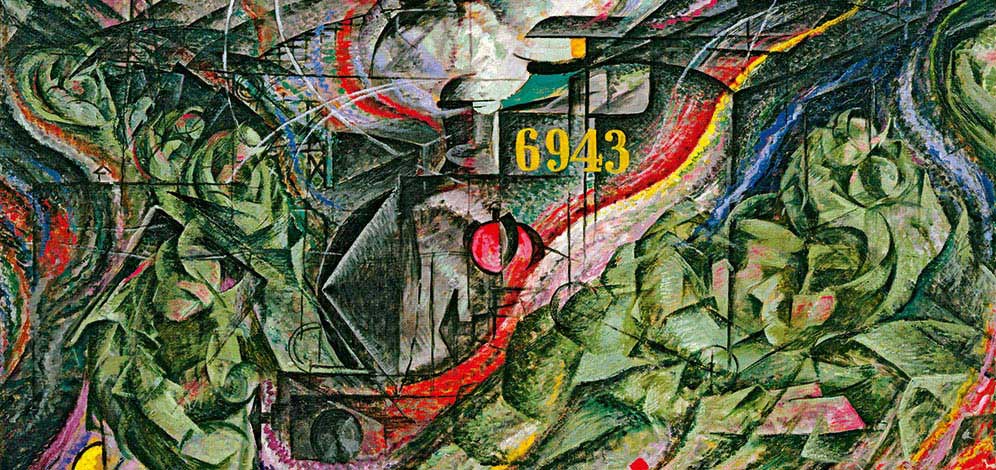

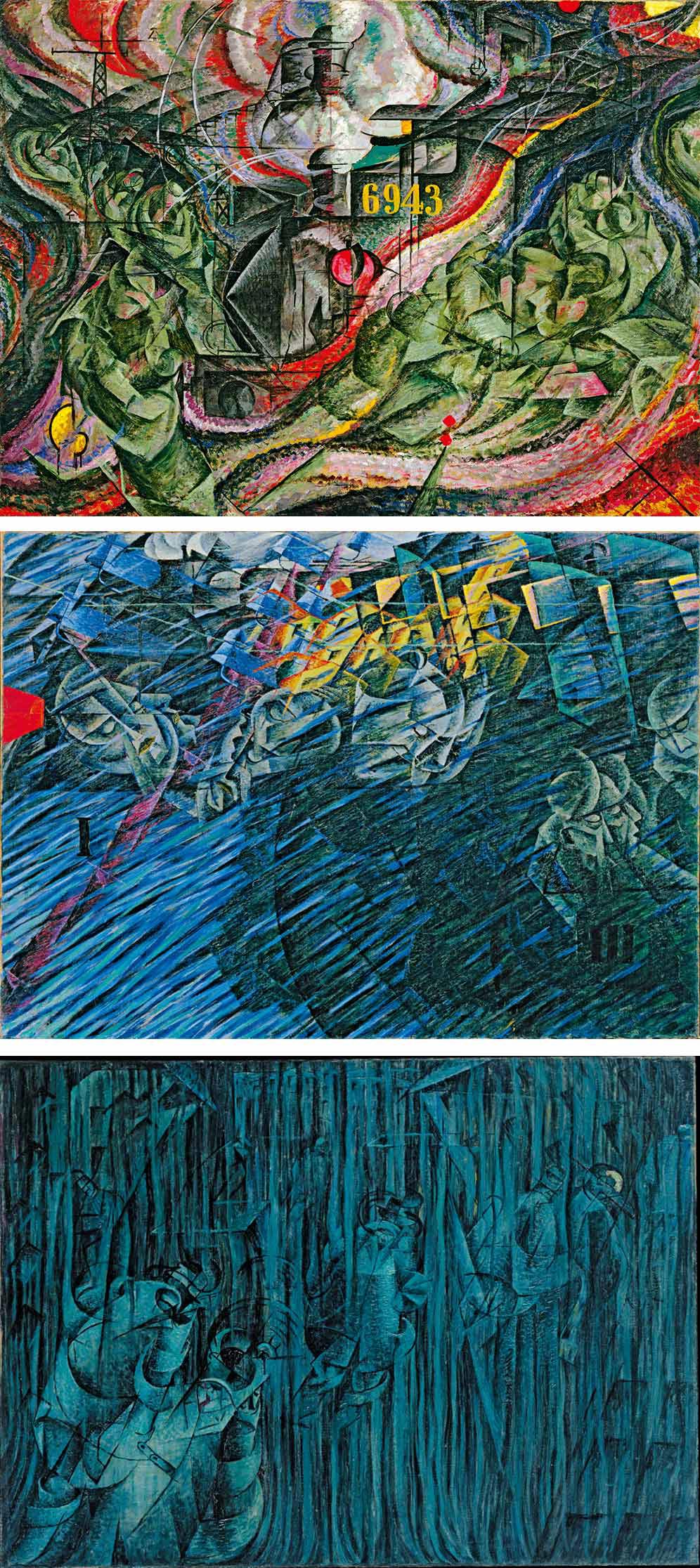

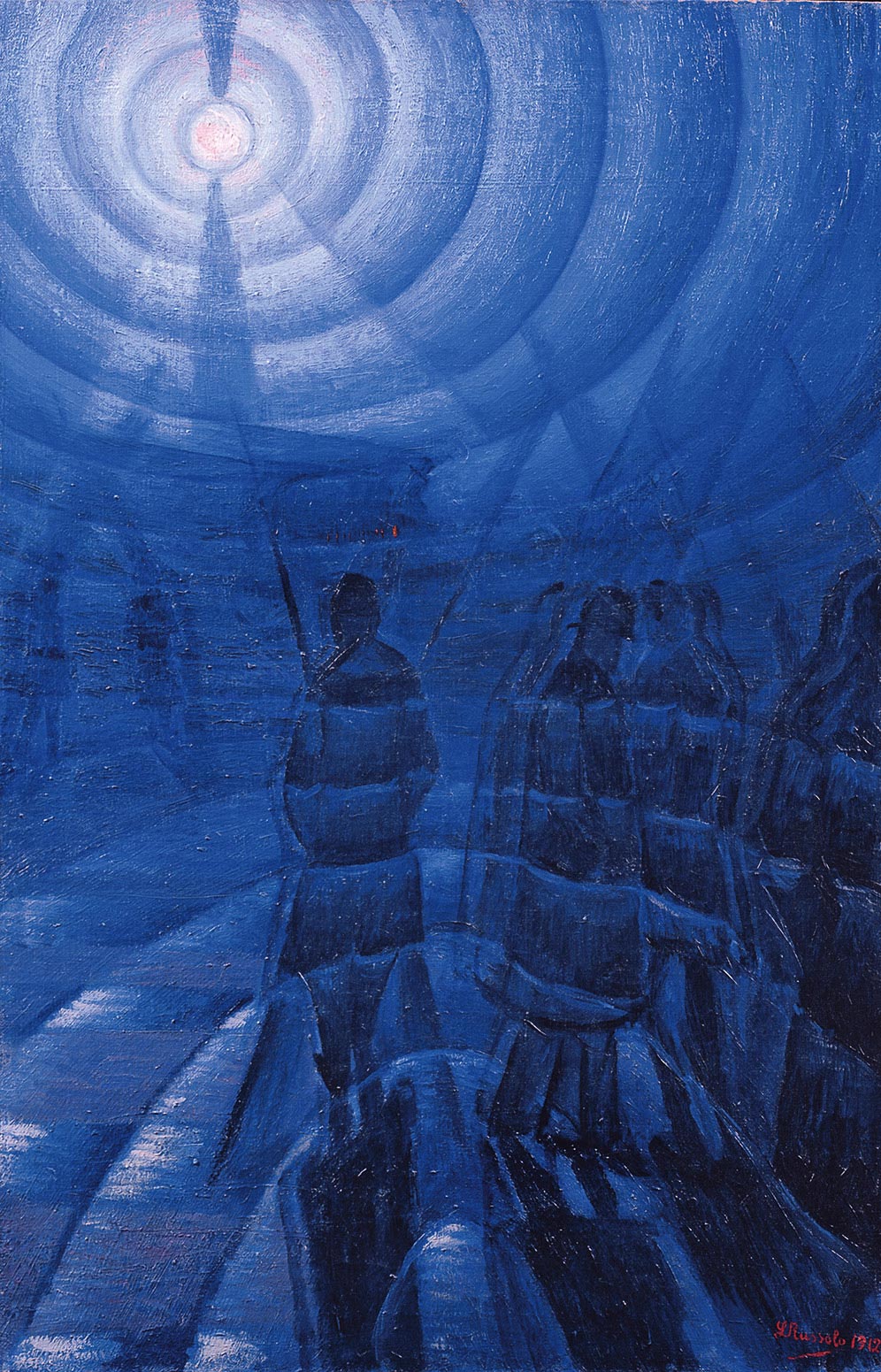

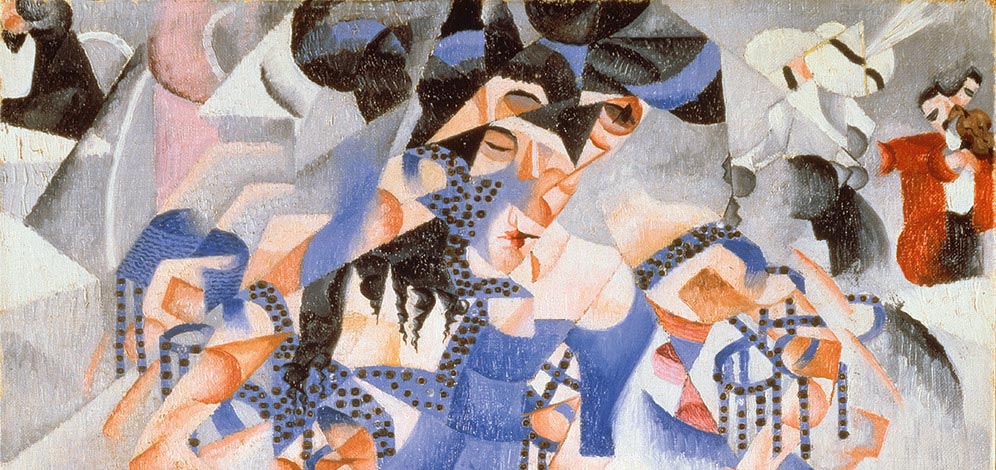

Futurist visual artists agreed that the representation of dynamism and simultaneity was tantamount, but were divided on how to achieve this. Giacomo Balla examined trajectories of movement. The Iridescent Interpenetrations, which are thought to illustrate light’s movement in electromagnetic waves, are his attempt to portray the universal dynamics that permit speed. These explorations informed his later Abstractions of Speed, a series prompted by the reflections of passing cars in shopwindows. Balla realized his own visual vocabulary for velocity by combining the Futurist principles of dynamism and simultaneity with allusions to light, sound, and smell. On the other hand, Umberto Boccioni and Gino Severini sought to represent the distorting effects of motion on a subject. Boccioni looked to the action of the athletic body, merging figure and ground in his activated renderings of a rider on a galloping horse and of a cyclist racing through a landscape. Severini’s exposure to Parisian cafes, cabarets, and dance halls compelled him to study movement through dance, painting fragmented, whirling forms.

Revolutionary literary and architectural experiments also occurred in these years. The Futurists pioneered a style of visual poetry they called parole in libertà, or “words-in-freedom.” Introduced by F. T. Marinetti, words-in-freedom was seized upon in the 1910s by Futurist painters and writers who produced confrontational, unorthodox sketches (tavole parolibere) on modern themes. In 1914 the architects Mario Chiattone and Antonio Sant’Elia each created a series of utopian (and unrealized) designs for the contemporary city. Incorporating new materials and accommodating rapid transport, they reenvisioned urban existence through a vanguard aesthetic based on technology.