Futurism originated with the 1909 publication of F. T. Marinetti’s founding manifesto, and manifestos remained integral to the movement throughout its existence. The manifestos excerpted below demonstrate the breadth of Futurist concerns and styles.

Please note that Annex Levels 5 and 7 (see Museum Map), which contain Benedetta's murals and major works by Giacomo Balla and Fortunato Depero, close August 20.

“The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism”

“The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism”

F. T. Marinetti

THE MANIFESTO OF FUTURISM

- We intend to sing to the love of danger, the habit of energy and fearlessness.

- Courage, boldness, and rebelliousness will be the essential elements of our poetry.

- Up to now literature has exalted contemplative stillness, ecstasy, and sleep. We intend to exalt movement and aggression, feverish insomnia, the racer’s stride, the mortal leap, the slap and the punch.

- We affirm that the beauty of the world has been enriched by a new form of beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car with a hood that glistens with large pipes resembling a serpent with explosive breath . . . a roaring automobile that seems to ride on grapeshot—that is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

- We intend to hymn man at the steering wheel, the ideal axis of which intersects the earth, itself hurled ahead in its own race along the path of its orbit.

- Henceforth poets must do their utmost, with ardor, splendor, and generosity, to increase the enthusiastic fervor of the primordial elements.

- There is no beauty that does not consist of struggle. No work that lacks an aggressive character can be considered a masterpiece. Poetry must be conceived as a violent assault launched against unknown forces to reduce them to submission under man.

- We stand on the last promontory of the centuries! . . . Why should we look back over our shoulders, when we intend to breach the mysterious doors of the Impossible? Time and space died yesterday. We already live in the absolute, for we have already created velocity which is eternal and omnipresent.

- We intend to glorify war—the only hygiene of the world—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of anarchists, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and contempt for woman.

- We intend to destroy museums, libraries, academies of every sort, and to fight against moralism, feminism, and every utilitarian or opportunistic cowardice.

- We shall sing the great masses shaken with work, pleasure, or rebellion: we shall sing the multicolored and polyphonic tidal waves of revolution in the modern metropolis; shall sing the vibrating nocturnal fervor of factories and shipyards burning under violent electrical moons; bloated railroad stations that devour smoking serpents; factories hanging from the sky by the twisting threads of spiraling smoke; bridges like gigantic gymnasts who span rivers, flashing at the sun with the gleam of a knife; adventurous steamships that scent the horizon, locomotives with their swollen chest, pawing the tracks like massive steel horses bridled with pipes, and the oscillating flight of airplanes, whose propeller flaps at the wind like a flag and seems to applaud like a delirious crowd.

F. T. Marinetti, “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism” (“Le Futurisme”). Published in Le Figaro (Paris), Feb. 20, 1909. Newspaper, 61.2 × 43.8 cm. Private collection © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome.

Translation courtesy Yale University Press, from Futurism: An Anthology, ed. Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009)

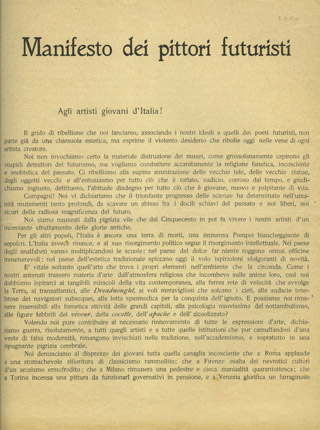

“Manifesto of the Futurist Painters”

“Manifesto of the Futurist Painters”

Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Giacomo Balla, and Gino Severini

Here are our final conclusions. With our enthusiastic adherence to Futurism, we want:

- To destroy the cult of the past, the obsession with antiquity, pedantry, and academic formalism.

- To disdain utterly every form of imitation.

- To exalt every form of originality, however daring, however violent.

- To bear bravely and proudly the facile smear of “madness” with which innovators are whipped and gagged.

- To regard all art critics as useless or harmful.

- To rebel against the tyranny of words: harmony and good taste, those too loose expressions with which one could easily destroy the work of Rembrandt and Goya.

- To sweep away from the ideal field of art all themes, all subjects that have been already used.

- To render and glorify today’s life, incessantly and tumultuously transformed by victorious science.

Let the dead stay buried in the deepest entrails of the earth! Let the threshold of the future be swept free of mummies! Make room for the young, the violent, the bold!

Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Aroldo Bonzagni, and Romolo Romani, “Manifesto of the Futurist Painters” (“Manifesto dei pittori futuristi”). Leaflet (Milan: Redazione di Poesia, 1910), 29.2 × 23 cm. Wolfsoniana–Fondazione regionale per la Cultura e lo Spettacolo, Genoa. Photo: Courtesy Wolfsoniana–Fondazione regionale per la Cultura e lo Spettacolo, Genoa

Translation courtesy Yale University Press, from Futurism: An Anthology, ed. Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009)

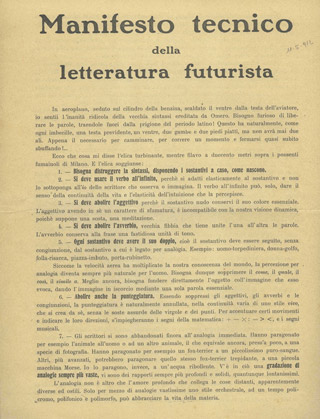

“Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature”

“Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature”

F. T. Marinetti

- It’s imperative to destroy syntax and scatter one’s nouns at random, just as they are born.

- It is imperative to use verbs in the infinitive, so that the verb can be elastically adapted to the noun and not be subordinated to the I of the writer who observes or imagines. Only the infinitive can give a sense of the continuity of life and the elasticity of the intuition that perceives it.

- Adjectives must be abolished, so that the noun retains its essential color. The adjective, which by its nature tends to render shadings, is inconceivable within our dynamic vision, for it is presupposes a pause, a meditation.

- Adverbs must be abolished, old buckles strapping together two words. Adverbs give a sentence a tedious unity of tone.

- Every noun must have its double, which is to say, every noun must be immediately followed by another noun, with no conjunction between them, to which it is related by analogy. Example: man—torpedo boat, woman—bay, crowd—surf, piazza—funnel, door—faucet.

- Just as aerial speed has multiplied our experience of the world, perception by analogy is becoming more natural for man. It is imperative to suppress words such as like, as, so, and similar to. Better yet, to merge the object directly into the image which it evokes, foreshortening the image to a single essential word.

- Abolish all punctuation. With adjectives, adverbs, and conjunctions having been suppressed, naturally punctuation is also annihilated with the variable continuity of a living style that creates itself, without the absurd pauses of commas and periods. To accentuate certain movements and indicate their directions, mathematical signs will be used: + - : = > <, along with musical notations.

- Until now writers have been restricted to immediate analogies. For example, they have compared an animal to man or to another animal, which is more of less the same thing as taking a photograph. (They’ve compared, for example, a fox terrier to a tiny thoroughbred. A more advanced writer might compare that same trembling terrier to a telegraph. I, instead, compare it to gurgling water. In this there is an ever greater gradation of analogies, affinities ever deeper and more solid, however remote.)

- Analogy is nothing other than the deep love that binds together things that are remote, seemingly diverse or inimical. The life of matter can be embraced only by an orchestral style, at once polychromatic, polyphonic, and polymorphous, by means of the most extensive analogies.

F. T. Marinetti, “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature” (“Manifesto tecnico della letteratura futurista”). Leaflet (Milan: Direzione del Movimento Futurista, 1912), 29.1 × 23 cm. Wolfsoniana–Fondazione regionale per la Cultura e lo Spettacolo, Genoa © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome. Photo: Courtesy Wolfsoniana–Fondazione regionale per la Cultura e lo Spettacolo, Genoa

Translation courtesy Yale University Press, from Futurism: An Anthology, ed. Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009)

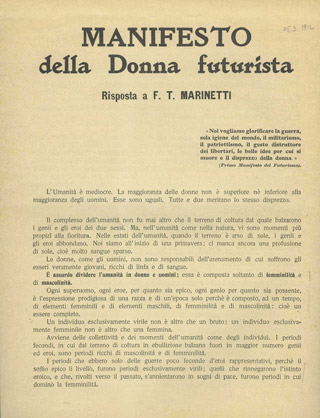

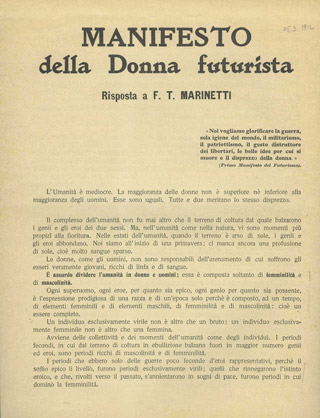

“Manifesto of the Futurist Woman”

“Manifesto of the Futurist Woman”

Valentine de Saint-Point

WE CONCLUDE:

The woman who keeps a man at her feet with tears and sentimentalism is inferior to the prostitute who impels a man, by prompting him to boast, to preserve his domination over the depths of the city with a revolver in his hand. This woman, at least, cultivates energy that could eventually serve better causes.

WOMEN, TOO LONG CORRUPTED BY MORALS AND CONVENTIONS, RETURN TO YOUR SUBLIME INSTINCT; TO VIOLENCE AND CRUELTY.

For the fatal enhancement of the race, while men are warring and struggling, you must make children; it is among them, in an act of sacrifice to the cause of Heroism, that you must play the part of Destiny.

Don’t raise them for yourself, which is tantamount to diminishing them, but let them grow in ample freedom, through complete development.

Instead of crushing man into bondage to EXECRABLE SENTIMENTAL NEEDS, impel your children and your men to surpass themselves. It is you who make them. You have complete power over them.

YOU OWE HUMANITY SOME HEROES. NOW MAKE THEM!

Valentine de Saint-Point, “Manifesto of the Futurist Woman: Response to F. T. Marinetti” (“Manifesto della Donna futurista: Risposta a F. T. Marinetti”). Leaflet (Milan: Direzione del Movimento Futurista, 1912), 29.2 × 23 cm. Wolfsoniana–Fondazione regionale per la Cultura e lo Spettacolo, Genoa. Photo: Courtesy Wolfsoniana–Fondazione regionale per la Cultura e lo Spettacolo, Genoa

Translation courtesy Yale University Press, from Futurism: An Anthology, ed. Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009)

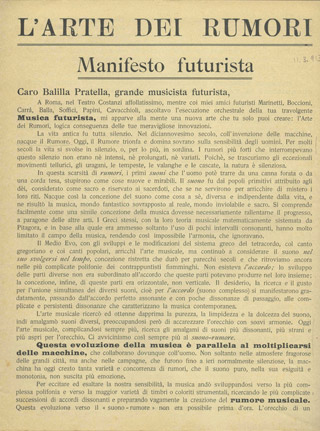

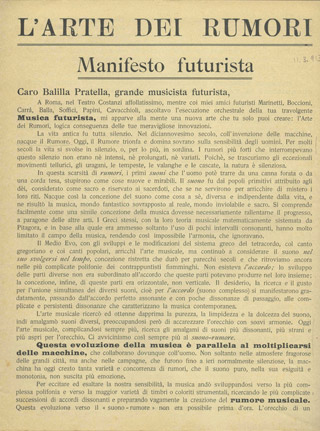

“The Art of Noises: Futurist Manifesto”

“The Art of Noises: Futurist Manifesto”

Luigi Russolo

This evolution of music is parallel to the multiplication of machines, which everywhere are collaborating with man. Not only amid the clamor of the metropolis, but also in the countryside, which until yesterday was normally silent, in our time the machine has created such a variety and such combinations of noises that pure sound, in its slightness and monotony, no longer arouses any feeling.

To excite and exalt our sensibilities, music has been developing toward extremely complex polyphony and the greatest possible variety of orchestral timbres, or colors, seeking out the most complex successions of dissonant chords, and preparing in a general way for the creation of musical noise. This evolution toward “noise-sound” was not possible before now. The ear of an eighteenth-century man could never have supported the dissonant intensity of certain chords produced by our orchestras (with three times as many performers as those of his day). Our ear instead takes pleasure in it, since it has already been trained by modern life, so teeming in different noises. Not, however, that it is fully satisfied: instead it demands an ever greater range of acoustical emotions.

Musical sound, on the other hand, is too limited in its qualitative variety of timbres. The most complicated orchestras are reduced to four or five classes of instruments, differing in timbre: instruments played with the bow, plucked instruments, brass winds, wood winds, and percussion instruments. So that modern music founders within this tiny circle as it vainly attempts to create new kinds of timbre.

We must break out of this restricted circle of pure sounds and conquer the infinite variety of noise-sounds.

Luigi Russolo, “The Art of Noises: Futurist Manifesto” (“L’arte dei rumori: Manifesto futurista”). Leaflet (Milan: Direzione del Movimento Futurista, 1913), 29.2 × 23 cm. Wolfsoniana–Fondazione regionale per la Cultura e lo Spettacolo, Genoa, used by permission. Photo: Courtesy Wolfsoniana–Fondazione regionale per la Cultura e lo Spettacolo, Genoa

Translation courtesy Yale University Press, from Futurism: An Anthology, ed. Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009)

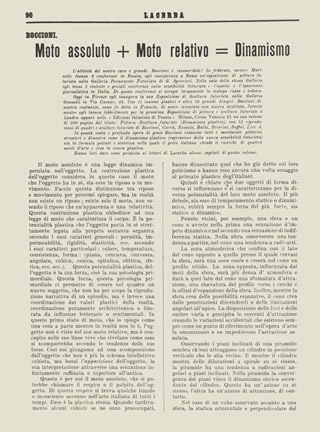

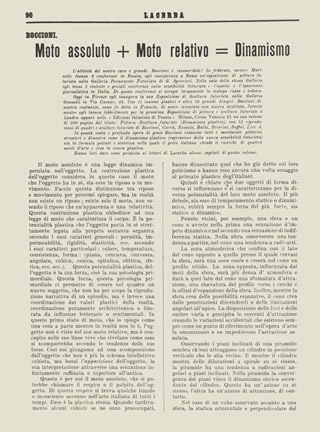

“Absolute Motion + Relative Motion = Dynamism”

“Absolute Motion + Relative Motion = Dynamism”

Umberto Boccioni

Absolute motion is a dynamic law that is inherent in an object. The plastic construction of the object, then, has to be concerned with the motion which an object has within itself, whether it be at rest or in movement. I’ve made this distinction between rest and movement so that I may make myself clear, although, in fact, there is no such thing as rest, only motion (rest being merely relative, a matter of appearance). This plastic construction obeys a law of motion which characterizes the body in question, a law that is the plastic potential which the object contains within itself, which in turn is strictly bound up with its own organic substance, as determined by its general characteristics (porosity, impermeability, rigidity, elasticity, and so on) and its particular characteristics, such as color, temperature, consistency, form (flat, concave, convex, angular, cubic, conic, spiral, elliptical, spherical, etc.). The plastic potential that resides in an object is its force, that is, its primordial psychology. This power, this primordial psychology, enables us to create in our paintings new subjects which do not aim at narrative or episodic representation; instead, it coordinates the plastic values of reality, a coordination which is purely architectural and remains free of all literary and sentimental influences.

“Absolute Motion + Relative Motion = Dynamism” (“Moto assoluto + moto relativo = Dinamismo”). Published in Lacerba 2, no. 6 (Mar. 15, 1914). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Library, New York. Photo: © Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Translation courtesy Yale University Press, from Futurism: An Anthology, ed. Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009)

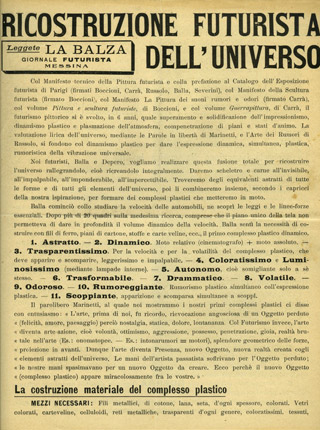

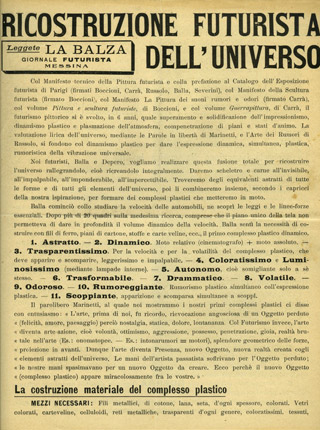

“Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe”

“Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe”

Giacomo Balla and Fortunato Depero

SYSTEMATIC INIFINITE DISCOVERY-INVENTION

by means of noise-ist constructive complex abstraction, which is to say, Futurist style. For us, every action that unfolds in space, every lived emotion will be the intuition of a discovery.

EXAMPLES: Watching the speedy ascent of an airplane, seen while a band was playing below in the square, we intuited the Plastic — Motornoise-ist Concert in Space and the Launching of Aerial Concerts above a city. —The need to vary one’s environment as often as possible and the idea of sports have enabled us to intuit Transformable Clothing (mechanical accessories, surprises, tricks, the disappearance of individuals). —The simultaneity of speed and noises has enabled us to intuit The Noise-ist Mobile-plastic Fountain. —Tearing up and throwing a book down into the courtyard has enabled us to intuit Phono-moto-plastic Advertising and Abstract-plastic-fireworks Contests. —A garden in the spring with a breeze has enabled us to intuit the The Motornoise-ist Transformable Magical Flower. —Clouds hurtling through a storm have enabled us to intuit The Transformable Building in Noise-ist Style.

Giacomo Balla and Fortunato Depero, “Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe” (“Ricostruzione futurista dell’universo”). Leaflet (Milan: Direzione del Movimento Futurista, 1915), 29.2 × 23 cm. Wolfsoniana–Fondazione regionale per la Cultura e lo Spettacolo, Genoa © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome. Photo: Courtesy Wolfsoniana–Fondazione regionale per la Cultura e lo Spettacolo, Genoa

Translation courtesy Yale University Press, from Futurism: An Anthology, ed. Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009)

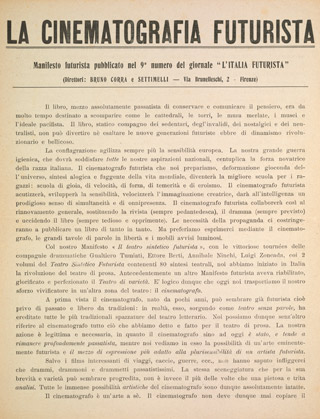

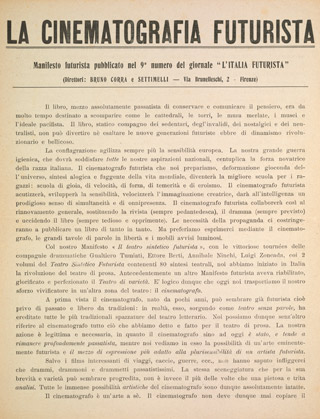

“The Futurist Cinema: Futurist Manifesto”

“The Futurist Cinema: Futurist Manifesto”

F. T. Marinetti, Bruno Corra, Emilio Settimelli, Arnaldo Ginna, Giacomo Balla, Remo Chiti

Film is an autonomous art. The filmmaker, therefore, must never copy the stage. Because it is essentially visual, cinema must above all fulfill the evolution that painting has undergone: detach itself from reality, from photography, from the graceful and solemn. It must become antigraceful, deforming, impressionistic, synthetic, dynamic, free-wordist.

We must liberate film as an expressive medium in order to make it the ideal instrument of a new art, immensely vaster and nimbler than all the existing arts. We are convinced that only thus can it attain the polyexpressiveness toward which all the most modern artistic researches are moving. Futurist cinema is creating, precisely today, the polyexpressive symphony that just a year ago we announced in our manifesto “Weights, Measures, and Prices of Artistic Genius.” The most varied elements will go into the Futurist film as expressive means: from the slice of life to the streak of color, from the conventional line of prose to words-in-freedom, from chromatic and plastic music to the music of objects. In short, it will be painting, architecture, sculpture, words-in-freedom, music of colors, lines, and forms, a clash of objects and realities thrown together at random. We shall offer new inspiration for painters who are attempting to break out of the limits of the frame. We shall set in motion the words-in-freedom that transgress the boundaries of literature as they march toward painting, music, the art of noises, as they throw a marvelous bridge between the word and the real object.

“The Futurist Cinema: Futurist Manifesto” (“La cinematografia futurista: Manifesto”). (Milan: Direzione del Movimento Futurista, 1916). The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (c) 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome. Photo: Courtesy The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Translation courtesy Yale University Press, from Futurism: An Anthology, ed. Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009)

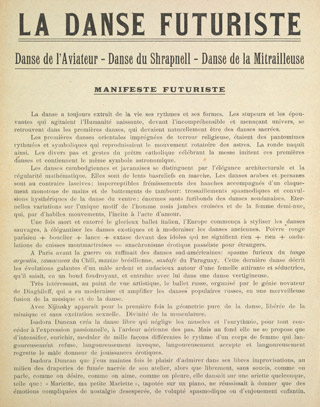

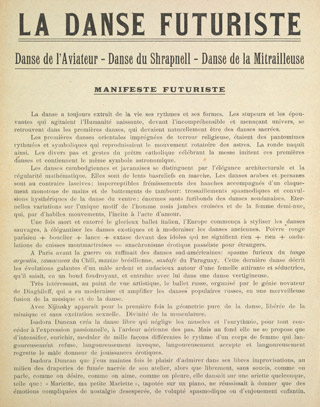

“Futurist Dance”

“Futurist Dance”

F. T. Marinetti

One must go beyond muscular possibilities and aim in the dance for that ideal multiplied body of the motor that we have so long dreamed of. Our gestures must imitate the movements of machines assiduously paying court to steering wheels, tires, pistons, and so preparing for the fusion of man with the machine, achieving this metallism of Futurist dance.

Music is fundamentally and incurably passéist, and hence hard to deploy in Futurist dance. Noise, because it results from the friction or the collision of solids, liquids, or gases that are in rapid motion, has become by means of onomatopoeia, one of the most dynamic elements of Futurist poetry. Noise is the language of the new human-mechanical life. Futurist dance, therefore, will be accompanied by organized noises and by the orchestra of noise-tuners which Luigi Russolo has invented.

Futurist dance will be:

- anti-harmonic

- ill-mannered anti-gracious

- asymmetrical

- synthetic

- dynamic

- free-wordist.

F. T. Marinetti, “Futurist Dance: Pilot Dance–Shrapnel Dance–Machine Gun Dance; Futurist Manifesto” (“La danse futuriste: Danse de l’aviateur–danse du shrapnell–danse de la mitrailleuse; Manifeste futuriste”). Leaflet (Milan: Direzione del Movimento Futurista, ca. 1920), 29.1 × 23.1 cm. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome. Photo: The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Translation courtesy Yale University Press, from Futurism: An Anthology, ed. Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009)

“Manifesto of Futurist Cooking”

“Manifesto of Futurist Cooking”

F. T. Marinetti

Pasta, which is 40 percent less nutritious than meat, fish, and vegetables, binds the Italians of today, with its knotty strands, to the languid looms of Penelope and to somnolent sails waiting for a wind. What is the point of continuing to let its heavy bulk stand against that immense network of long and short waves that Italian genius has flung over the oceans and continents, against those landscapes of color, form, and sound with which radio-television circumnavigates the Earth? The apologists for pasta carry its leaden ball, its ruins, in their stomachs, like prisoners serving a life sentence, or archaeologists. Bear in mind too that the abolition of pasta will liberate Italy from the costly burden of foreign grain and will work in favor of the Italian rice industry.

We invite the chemical industry to do its duty and, very soon, provide the body with all the calories it needs by means of nutritional equivalents, supplied free of charge by the State, in the form of pills or powders, albuminous compounds, synthetic fats, and vitamins. We shall thus arrive at a real reduction in the cost of living and of wages, with a corresponding reduction in the number of working hours. Today, the production of 2,000 kilowatts requires only one workman. Machines will soon constitute an obedient workforce of iron, steel, and aluminum at the service of mankind, which will be relieved, almost entirely, of manual labor. This being reduced to two or three hours, will allow the refinement and the exaltation of the other hours through thought, the arts, and the anticipation of perfect meals.

F. T Marinetti, “The Manifesto of Futurist Cooking” (“Il Manifesto della cucina futurista”). (1930) Published in La cucina futurista (Milan: Sonzogno, 1932). Rovereto, MART, Archivio del ’900. (c) 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome. Photo: (c) MART, Archivio del ’900

Translation courtesy Farrar, Straus and Giroux, from F. T. Marinetti, Critical Writings, ed. Günter Berghaus, trans. Doug Thompson (2006)